Product Details:

- Format: Hardback

- Publication Date: August 2024

- Price: €35 / €40 CD Included

- Publisher: Agram Blues Books

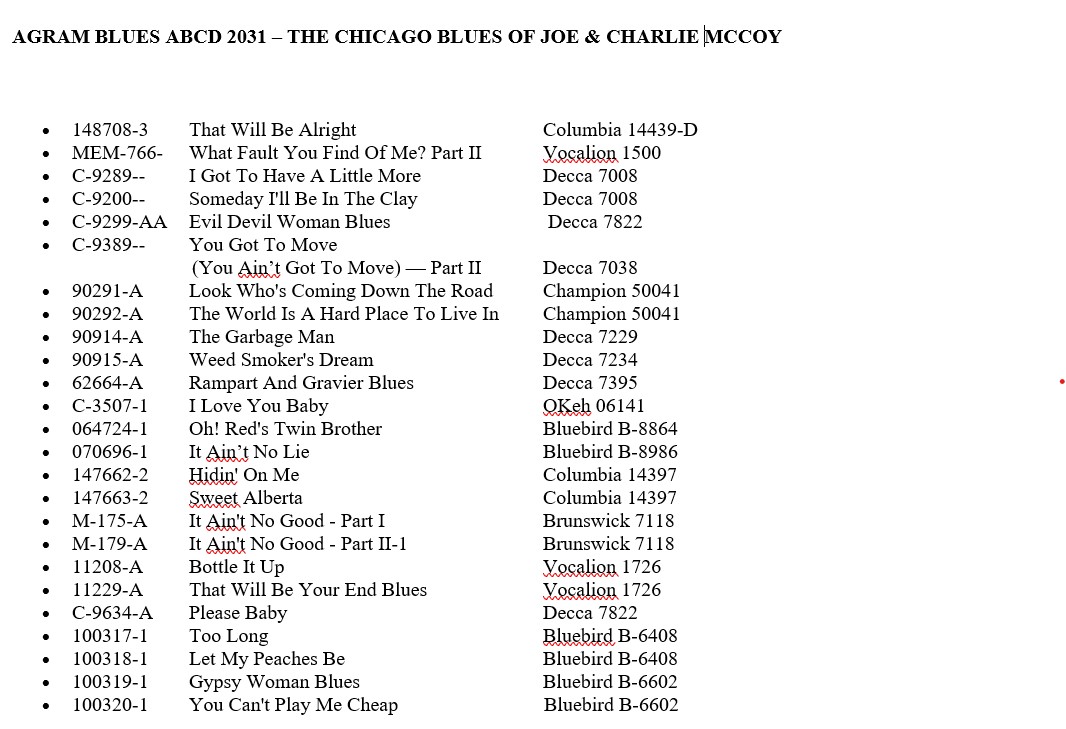

Of all the books in this series by Guido van Rijn, this study of the lives, musical styles, and recordings of “blues brothers” Joe and Charlie McCoy has been the most problematic and difficult to bring to completion and publication. Some of the problems were simply due to the volume of material the two artists recorded, the difficulty of obtaining listenable copies of some songs, and further difficulties of understanding their lyrics, the latter especially in the case of brother Joe. For two artists who recorded prolifically, both separately and together, over a period of about a decade and a half, and who composed and/or performed on many hit records, the McCoy brothers are little mentioned by others who knew them and are generally mentioned only in passing by blues researchers. They remain unjustifiably in the shadows of blues history, while their contemporaries and collaborators, such as Bo Carter, Tommy Johnson, Ishman Bracey, the Mississippi Sheiks, Memphis Minnie, Big Bill Broonzy, Washboard Sam, Johnnie Temple, Tampa Red, and Roosevelt Sykes, shine brightly in the blues firmament.

Charlie, the younger of the two, was the first to record, in 1928 as guitar or mandolin accompanist to Tommy Johnson, Ishman Bracey, and Rosie Mae Moore. He was only a teenager at the time and was viewed as a musical prodigy by the more established blues musicians of Jackson, Mississippi, where he had gotten his start. By 1932, barely an adult, he was being billed on record labels as “Papa” Charlie McCoy. Despite having his name as artist and composer on the labels of two songs that became blues standards, “Corrine Corrina” (1928) and “Bottle It Up” [and Go] (1932), he seems to have been unable to parlay this early artistic success into fame and fortune. His songs were generally good from a compositional standpoint, his diction clear, his voice pleasant, and his performances excellent, but he never really emerged as a distinct personality and star. Instead, he remained in the background, serving mainly as a versatile and much-in-demand accompanist to other artists, many of whom were or became better known. By the early 1940s his mandolin sound had become passé in the blues, and he seems never to have adapted to the electric guitar, although undoubtedly he had the talent and ability to do so. We may never know whether he preferred to remain in the background or was simply the victim of bad luck and the vagaries of fame and fortune, like so many other talented artists and musicians, or whether there was something in his personality or lifestyle that prevented him from earning the reputation and stature he so richly deserved. Sadly, Charlie McCoy’s career declined precipitously in the 1940s when blues styles were evolving rapidly, and he died in obscurity in 1950.

Beginning in 1929, Joe McCoy recorded as a vocalist and guitarist. He was even more prolific as a featured recording artist than his younger brother Charlie, but he still remains a vague personality to blues fans and historians. In his case, it seems to have been due to a somewhat domineering and self-indulgent personality that is sometimes reflected in his song lyrics and that perhaps alienated him to others as well as to some modern listeners. But he also seems to have deliberately courted personal obscurity while at the same time courting commercial success. He never recorded under his real name of Wilber McCoy, instead using close to a dozen pseudonyms and nicknames or subsuming himself under the names of groups that he headed. Even the name “Joe” McCoy, which he seems to have adopted as his own, is found on record labels only in composer credits but never as the name of the actual recording artist. Although he is heard, often as a featured artist, on such classic and frequently covered blues songs as “When The Levee Breaks,” “Bumble Bee,” “I’m Talking About You,” “What Fault You Find of Me?,” “Can I Do It for You?,” “What’s The Matter With The Mill?,” “Oh! Red,” “Move Your Hand,” “Sales Tax On It,” “The Garbage Man,” and “Why Don’t You Do Now,” many of which he also composed or co-authored, he never seemed to emerge as one of the major stars of the blues in the 1930s, his most prolific decade. Part of this may be due to the lasting fame of his first recording partner and spouse, Memphis Minnie, who was a flamboyant personality in her own right and certainly his equal as a singer, guitarist, and songwriter. But it must also have been due to his decision to spread his fame and notoriety over so many aliases and group names. No one has ever come up with an explanation for why he did this. He died in the same year as his brother, in equally obscure circumstances.

Problems and gaps remain in our knowledge of these two artists, and many of them may never be resolved. Nevertheless, Guido van Rijn, as in his previous studies of prolific but somewhat overlooked blues greats Smokey Hogg, Walter Davis, Washboard Sam, Leroy Carr, and Jazz Gillum, does the most thorough and best possible job of pulling together scattered biographical references to the McCoy brothers as well as accurately transcribing and explaining their song lyrics and adding an understanding of their musical styles. As a result, these two artists are elevated to the level of greatness that they deserve.

Professor Emeritus of Music,

The University of Memphis